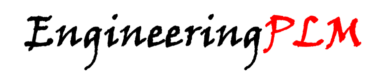

In the world of manufacturing, we often talk about “the truth.” We want a single source of truth, a definitive bill of materials (BOM), and a clear path from design to the shipping dock. But what happens when that “truth” includes things that don’t actually exist?

Welcome to the paradoxical world of Phantom Assemblies.

If you work in engineering, a phantom assembly sounds like a mistake—a grouping of parts that never actually gets built as a standalone unit. But if you work in production planning or finance, that same phantom is a vital tool for keeping the assembly line moving and the costs accurate.

Managing this “ghost in the machine” is one of the most common friction points between Product Lifecycle Management (PLM) and Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP). If you get it right, your production is seamless. If you get it wrong, you end up with “inventory ghosts” that haunt your warehouse and wreck your margins.

What Exactly is a Phantom Assembly?

At its core, a phantom assembly is a logical grouping of parts that are physically built during a higher-level assembly process but are never stocked as an individual sub-assembly.

Think of a bicycle. You might have a “Brake Cable Set” consisting of the inner wire, the outer housing, and the end caps. In your engineering design (PLM), it makes perfect sense to group these together. However, on the factory floor, the worker doesn’t grab a pre-assembled “Cable Set” from a bin. They grab the wire, the housing, and the caps separately and install them directly onto the frame.

In this case, the “Cable Set” is a phantom. It exists in the documentation to make the design easier to manage, but it “blows through” in the ERP system, meaning the requirements for the individual components drop down to the next level of the manufacturing order.

Why Engineers Love Them (and Why Operations Needs Them)

The disconnect usually starts with how different departments view a product.

The Engineering Perspective (PLM):

Engineers use phantoms for modular design. If you’re designing a complex piece of machinery, you don’t want a flat list of 5,000 parts. You want to group them into functional modules (the electrical kit, the fastening hardware, the labeling set). It makes the CAD models manageable and allows for easier “Save As” workflows for future projects. To an engineer, the phantom is a container for design intent.

The Manufacturing Perspective (ERP):

Operations uses phantoms for logistics and costing. If they were to treat every engineering group as a real sub-assembly, they would have to:

- Create a unique part number for the sub-assembly.

- Issue a separate work order to “build” the phantom.

- “Receive” the phantom into stock.

- “Issue” it back out to the main line.

That is a mountain of unnecessary paperwork for something that is never actually sitting on a shelf. By marking it as a “Phantom,” the ERP system knows to ignore the sub-assembly itself and go straight to the “children” parts for purchasing and scheduling.

The Cost of Mismanagement: When Phantoms Turn Into Poltergeists

The trouble begins when PLM and ERP aren’t speaking the same language. If a phantom is defined in engineering but not correctly flagged in the ERP, the system will sit there waiting for a “Brake Cable Set” to arrive in the warehouse. Meanwhile, the individual wires and caps are sitting in the bin, but the system won’t tell the worker to use them because it’s looking for the higher-level assembly.

Production grinds to a halt. The “ghost” has become a literal roadblock.

The “Hidden” Data Gap

The biggest challenge is the BOM Transformation. Engineering BOMs (EBOMs) are organized by function. Manufacturing BOMs (MBOMs) are organized by consumption.

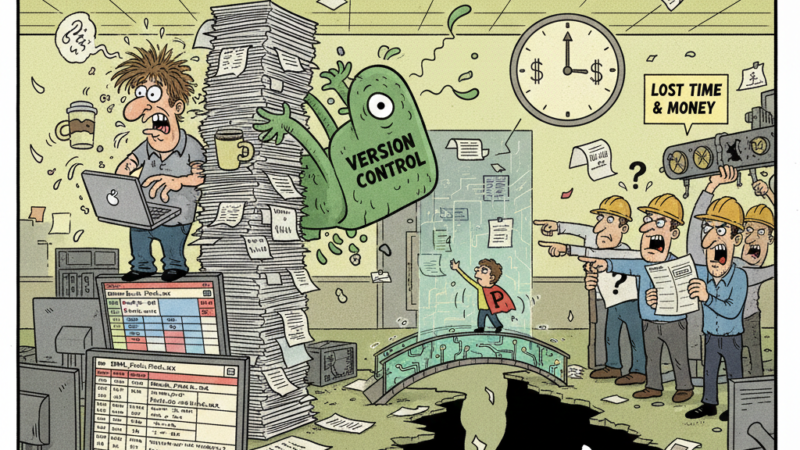

If your PLM system doesn’t have a clear way to flag a part as a phantom, the person responsible for the ERP upload has to manually identify and “blow through” those assemblies. This manual step is where 90% of the errors happen. You end up with “phantom” inventory—the system thinks you have 100 units of a sub-assembly that doesn’t exist, while your actual raw material counts are completely wrong.

Best Practices: How to Manage the Non-Existent

So, how do you keep your phantoms under control? It requires a blend of clear policy and smart technology integration.

1. Standardize the “Phantom Flag”

Your PLM and ERP must share a common attribute. Whether it’s a checkbox labeled “Phantom” or a specific “Procurement Type” code, this flag must be set in the PLM by the engineer and mapped directly to the corresponding field in the ERP. There should be zero manual interpretation during the data hand-off.

2. Master the “Blow-Through” Logic

Ensure your ERP is configured to handle the costing of phantoms correctly. Typically, the cost of a phantom is simply the sum of its components. However, some companies forget to account for the labor involved in installing those components at the higher level. If the labor isn’t attached to the parent assembly, your “true cost” of the product will be skewed.

3. Use Phantoms for “Common Kits”

Phantoms are incredibly useful for managing common hardware or “packaging kits.” If every product you ship includes a specific set of manuals, tools, and warranty cards, make that a phantom assembly. It keeps the design clean, but ensures the stockroom always knows exactly how many manuals to buy based on the total product demand.

4. Audit Your “Ghost Inventory”

Regularly run reports in your ERP to find any assembly that is flagged as a phantom but has an “On Hand” balance. If a phantom has inventory, something has gone wrong in your process—likely a return or a manual adjustment that shouldn’t have happened. These are the “ghosts” that ruin your year-end audits.

The Human Element: Bridging the Departmental Divide

Beyond the software and the flags, managing phantoms is a people problem. It requires the engineer to understand how a product is actually built on the floor, and it requires the production planner to understand why the engineer grouped those parts together in the first place.

I’ve seen companies solve this by having “BOM Review” meetings where engineers and shop floor leads look at the assembly structure together. When the shop floor lead says, “We never pre-build that,” the engineer knows exactly where to put the phantom flag.

Conclusion: Embracing the Ghost

Phantom assemblies might be “non-existent” parts, but their impact on your business is very real. They are the bridge between the conceptual world of design and the physical world of the factory floor.

When you manage them correctly within your PLM-to-ERP pipeline, you eliminate the friction of manual data entry, ensure your costing is accurate, and keep your production lines moving. You turn a potential source of “Excel Chaos” into a streamlined, automated workflow.

Don’t fear the ghosts in your system. If you give them the right structure and a clear voice in your “single source of truth,” they will become one of your most powerful tools for managing modern manufacturing complexity.